A long bicycle ride with sleep deprivation, including werewolves and an acid house party. My memory has become like clothes at a jumble sale: everything is there but the organisation is a mess. I’m writing this memoir as much to untangle my mind as to share the experience of this French ride.

Starting at the start: I recall the way the exhibitor’s tents created a patch of shade to pause in, prior to crossing the start line. Others in my group moved around me to get as close to the line as possible. The organisers had found someone with a strong voice and unmatched enthusiasm to send each wave of cyclists off with a cheer.

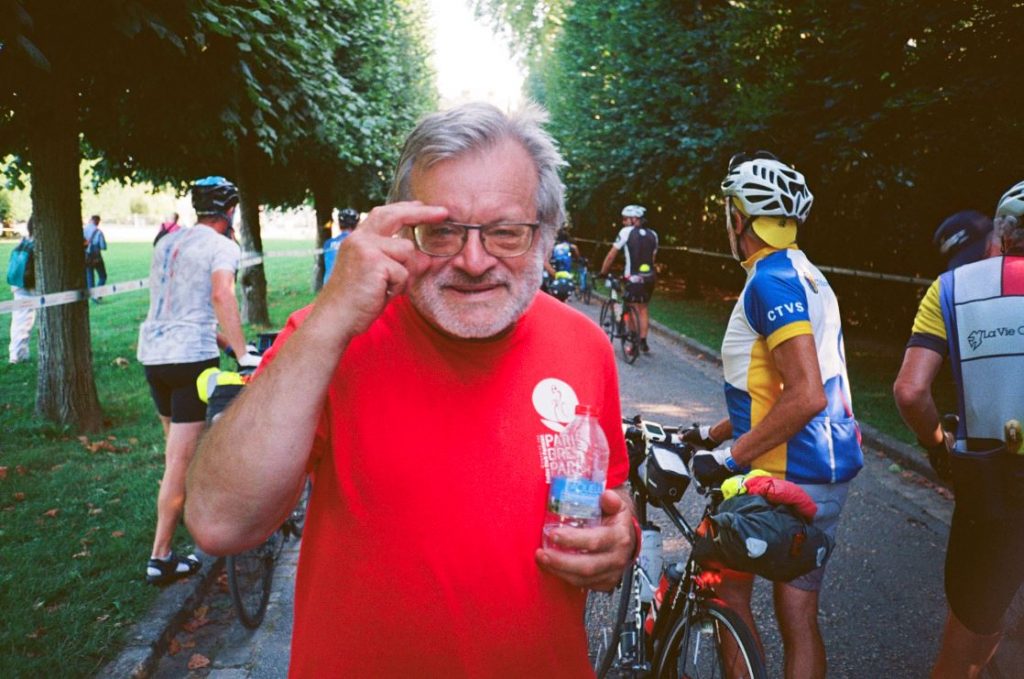

The journey to the start was much longer than the queue from the bike check. Paris-Brest is the biggest festival of endurance cycling in the world, attracting increasing numbers of riders year on year. In 2023 there were over 6700 entries from across the world and it is a pilgrimage many months in the making. “The French ride” comes across the radar of most long distance cyclists eventually, but not everyone is able to so order their lives as to meet the criteria to be on the start line. This is a ride in France, organised by the French. If you want to do it, you’ll need to prove yourself. Riding your bicycle a long way, is, for long distance cyclists, the easy part of qualifying. There are family and work commitments which may have to take a back seat to your Paris-Brest aspirations. I believe that merely making the start line qualifies a person to wear the Paris Brest Paris trophy jersey, because it represents an achievement of itself.

I’m an experienced long distance cyclist. That basically means I have the time and patience to go for a bike ride and not stop for a while. I do okay but I’m not winning any awards for style or speed. On the start line of Paris-Brest I was nervous. It was 7:15pm and I was setting out knowing that my body would be asked to take me into the night, through the cold of dawn, and carry on for as long as possible into the next night. Fatigue was going to feature prominently.

I’d travelled down with others, and we had booked an Air BnB 8km from the start at Rambouillet. Aidan Hedley, David Crampton, Robert McCready and I had a chilled Sunday, dozing and taking advantage of the shade. My cycling clubmates, VC167, and my travelling companions were mostly setting off earlier than me. I was happy to meet the friendly face of Chris Crossland who was volunteering at the start and carrying out bike checks. I said I was a bit nervous, and he said, “Quite right, it is the hardest thing you’re ever going to do.” Thank you Chris.

As the time came to begin my adventure, I rode away from the enthusiastic announcer surrounded by hundreds of others: three, four, five abreast, and pedalling over the smooth French tarmac out into the evening.

During one of my qualifying rides, I had fallen off my bike due to a misunderstanding with the riders around me. That had been a valuable learning experience, as now I watched the riders around me carefully and made sure I wasn’t at risk of a collision. Although I saw no collisions, I know that they happened. The early stages of this ride were hazardous.

I tried to start up the odd conversation, while bearing in mind that I couldn’t be certain if the riders near me even spoke English. I met Jessica Conner (Swindon Wheelers) and we chatted for a bit. I noticed that to her right was a Reading Cycling Club rider (I later discovered was Timothy Maw). Telbert James (Audax Club Bristol), was riding a fixed gear bike on the front and together they gave me the impression I was on the M4 corridor leaving London: they’d set a high enough pace.

The volume of cyclists and the awareness of the local people meant that we hardly paid much attention to road signs. As we came to each village there would be crowds cheering us on, and volunteers (each in a yellow jacket), waving us through junctions and roundabouts. It was clear throughout Paris-Brest that the people in the towns and villages along the route were completely immersed in the experience, treating the event as a good excuse for a street party – it almost felt like I cycled the whole route through one long celebration.

Most of the early route was along straight roads with smooth surfaces, and this made it as safe as it could be. The sun was bathing us as it slowly hit the horizon, giving us warmth that would last well into the night. I pulled to one side to put on my highly visible and reflective gilet.

Long distance cycling is not built on trust. We can’t just claim to have ridden a long way without the evidence to support our ridiculous experience. We each have a Brevet Card and a timing chip. The timing chip is scanned as we arrive at each control point, and our Brevet Cards are stamped by local officials.

The first Control Point on Paris-Brest is at Mortagne-au-Perche, 120km from Rambouillet. It was just past midnight, and I felt like I’d stumbled upon a 1990’s acid house party for the ‘gilets jaunes’. There was music, what seemed to be a BBQ, and a festival bar and people milling around in all directions. I knew I wasn’t supposed to be wasting time, but I was disoriented. I managed to refill my water bottles from the stop-taps beside the wooden pallets, I did get my Brevet Card stamped, but then instead of just leaving I panicked – had I missed something? Was I supposed to be doing something else? What was everyone else doing? I ate a pre-prepared chicken sandwich from my Carradice Barley and composed myself. I was fine. I just needed to leave. I think I must have spent at least 30 minutes there, much more than I would have done at the first Control Point on a UK Audax.

As the sounds of chaos dwindled behind me, I felt myself regain purpose. I have wanted to ride Paris-Brest for many years, and here I am doing it. When I’m finished it will be over and the thing I wanted to do will be no more. So, Graeme, immerse yourself in the experience and just ride.

It was the depths of the night, and I could see nothing except a snaking line of red rear lights hugging the contours of the countryside ahead of me. An unbroken line of red ahead, and glancing back, an unbroken line of sparkling white lights behind. I wondered if Paris-Brest was visible from space. I hope there is drone footage somewhere. Whether it was the lazy-Sunday napping before the start, or the adrenaline of the event, I didn’t feel tired and due to the number of riders, I couldn’t get lost. All I had to do was ride. Time passed in the darkness, and I didn’t notice. The night was warm: I wore shorts and a short-sleeved jersey without a hint of chill.

I arrived at the second Control Point, Villaines-la-Juhel (200km covered) at 4am. I had prepared myself for the chaos and focussed on getting my card stamped and refilling my water bottles. I chose not to eat, it seemed too crowded, and I was conscious that I didn’t want to spend a long time queuing for food. I got back on the bike and headed straight out into the night once more.

Those who aspire to complete Paris-Brest tend to seek advice from those who’ve completed it before. I understood that the wisest way to ride was to “race out and tour back”, basically: get to Brest as quickly as possible (in one go even) and then enjoy a more relaxed pace back.

As I left Villaines-la-Juhel I felt my spirits drop. I’d just done 200km as fast as ever, how was I going to keep going? I’d not eaten. That was silly. As I reached the edge of the town there was a car park with stalls selling food and hot drinks. I pulled over to get something to eat. My heart was sinking within me; I doubted my capability to complete this ride. I munched on a pain au chocolat, and then also a pain au raisin. I drank some coffee. If someone had offered to pop me in a campervan with my bike, and drive me back to the start, I wouldn’t have hesitated. I would have quit. At that moment, Shaun Hargreaves (Four Corners Audax), arrived. I shared my anxiety with him and was at once encouraged. Shaun reminded me that I would have ups and downs, but that in the end I was perfectly capable of getting to the end, “just keep pedalling” he may have said, waving me off.

I don’t know whether it was the pastry, Shaun’s encouragement, or the sunrise – but I felt ebullient. The sun was up, and the morning was fresh. The road undulated through fields and beautiful villages with cheering crowds. I was still surrounded by cyclists and reached Fougères (292km) at 8:30am. 13 hours to cycle 300km – again I was still riding much faster than I do in the UK, even with my mini-meltdown.

I wasted some time at Fougères. I tried to get an exemption certificate from the medical team so I wouldn’t have to wear my helmet anymore. I don’t normally wear a helmet, and Paris-Brest doesn’t normally require riders to. However, ten days before the start, we’d all received an email telling us helmets were mandatory. For those who wear helmets this is no big deal, but if you haven’t worn one for a decade – and don’t even own one – then this is problematic. I was only beginning to get used to my brand-new helmet, and would have preferred to be simply wearing a cotton cap. I wanted someone to understand, and to give me permission to carry on without it. I sat and smiled while a heated conversation took place between three French officials before the doctor finally told me that I could indeed have a medical exemption certificate. Hurray! However, I would then be disqualified. I had a feeling that the word “exemption” had been lost in translation. Although I had spent the best part of an hour messing around on this subject, I don’t regret it, because it would have made the rest of the ride so much easier. I left Fougères without eating.

The morning was warm and sunny, my attempt to subvert the rules had encouraged me and I was refreshed – if not from eating then from the hour off the bike. It was only 60km between Fougères and Tinténiac, but I fancied some supermarket food. Other riders were sat in front of “Market” at Saint-Aubin-du-Cormier, so I joined them. I wandered around the supermarket looking for food and drink, finding a smoothie, chicken sandwiches and a couple of bananas. I also availed myself of the toilet facilities… they were clean when I went in, and clean when I left dear reader.

With my water bottles refilled again, I continued to Tinténiac, arriving at lunchtime. I knew that this time I needed some food, but I was also feeling quite relaxed and happy with the ride so far. 352km in 16 hours including my silly time-wasting incidents. I left in the early afternoon heading for Loudéac. The afternoon temperature reached 33C and the sky was completely clear of clouds. There wasn’t a breath of wind, and the heat became oppressive. At Saint-Méen-le-Grand I called into a McDonalds for an ice-cream and coke, but their machines weren’t working. I was feeling empty and slow, my spirits were low. The ride to Loudéac was so achingly slow, finding water wherever I could and trying to balance my salt levels by drinking water with rehydration tablets.

On the way to Loudéac I decided that it would be wise to get some sleep in the late afternoon, and then cycle on in the night when it would be cooler, and when I would be refreshed. Loudéac couldn’t arrive quick enough. As wonderful as I had felt in the morning ride to Fougères: I was feeling equally and oppositely awful in the afternoon to Loudéac. It was 5pm when I reached the Control, 440km from the start and still beating any previous best times for these distances.

There was a sports hall, and it was empty. I was the first person to request a sleep. I knew this wasn’t a mistake. Although others might be riding further into the night, and although received wisdom said keep going to Brest, I knew that if I sheltered from the heat now I’d easily get through the next night. I had two hours perfect sleep on a camp bed and woke up fresh and without any aches or pains. All was well, so I went looking for a good meal. I was even more delighted when told that the long queue was for the hot food, if all I wanted was a baguette, pastry, cold drink and coffee: then the second dining room was empty, and no queue.

There was a lady pouring the coffee from a jug which was larger than she was. She was clearly struggling, and I was in high spirits and offered to help. It was a heavy pot of coffee and as I supported it with my left hand, I instantly realised I’d scalded my fingers. I put the pot down. I looked at the women behind the counter and suddenly the pain of the scald hit me, I cried out and ran into the kitchen, past the volunteers and found the first tap I could use to cool my burning fingers. My idiocy was kicking me in the head. A French woman came up to me and took my hand out from under the tap. I snatched it back and put it under the tap. She switched the tap off and took my hand out… I protested and she tried to reassure me. She held her hand above mine and gently breathed on my fingers… I couldn’t believe it. I took my hand back and put it under the tap. In this way we fought to treat the scald. We argued in a mixture of bad French and broken English. Eventually I could do nothing but surrender to her. She was the single most wonderfully reassuring person I’d met, she obviously cared, and I desperately wanted to put my fingers under the cold tap, knowing that blisters on my fingers would make shifting gear really painful. She won though. The pain was subsiding, and she brought me back to find my baguette, drinks, Carradice, bottles and wallet. I sat there, eating and berating myself for being so stupid. I texted my wife for the first time in the ride:

I’m so utterly exhausted and on the edge of tears. I scalded the tips of my fingers in the cafeteria. And I’m tired. And hot. And I just want to quit. And I want to cry. And I’m a fifty year old man who did this to himself.

text message

What can I say though, her ministrations worked. I never got a blister, the pain did subside and I never paid the price for scalding myself. I still don’t really know how she did it, but my grateful heart and my prayers go out to her wherever she is. I have no idea what time I left Loudéac, yet despite the incident with the coffee pot, I was getting ready to cycle through the night.

Choosing what to take on a long ride is a wonderful game – but isn’t the same for everyone. There are as many different ideas about luggage as there are riders. Riders themselves seem to fall into several categories. First come the endurance racers, the Vedettes: they pack next to nothing. They have no plans to stop for longer than a Brevet Card stamp, a bottle refill and to go again. The quickest rider this year managed to get from Paris to Brest and back in about 42 hours. Some of them may have support from friends and family – their goal is to complete the event in the shortest time they can manage. After the Vedettes come the Randonneurs: experienced long distance cyclists who tend to look after themselves and carry everything they need. Finally come the Tourists, who are also accomplished Randonneurs, but those for whom the experience is more important than the time. I am firmly in the Tourist category, as evidenced by what I packed:

Night riding on Paris-Brest is difficult to describe. On the one hand there is nothing but the forever lights of other riders, yet there is also the disorientation of reflective yellow gilets that are difficult to focus on. No riders were allowed flashing rear lights, but some had them anyway. I found that none of the hills were difficult or steep, and that it kept me warm to ride slightly uphill. I remember the secret control at Canihuel and stopping for more food at midnight – the pasta was especially good. I was slow through the night and starting to worry that I wasn’t good enough to be doing this.

It was 2am on Tuesday morning when I reached Carhaix, and it was the most surreal experience I’ve ever had. I went to find food but couldn’t reach the kitchen. The benches, floors and even the tables had exhausted cyclists sleeping all over them. The food choices made very little sense either – the volunteers seemed almost as exhausted as the riders. I dawdled at Carhaix. I was in and out of the building looking for places to refill my water, a place to snooze, a place to eat. Apart from eating, I did very little useful. I did have a wonderful conversation about cotton caps and thought I would be riding with a fellow cap-wearer, until he turned east for Paris, and I turned west for Brest. That was my first interaction with someone from the pointy end of the ride.

My cycling club is VC167, but most of my clubmates had qualified for much earlier start times than me. The only club mate I kept bumping into was Chris Delf – he’d usually be leaving a Control as I arrived. I don’t mind riding alone on audaxes, or chatting to strangers, but I was never fully alone on Paris-Brest, as there was always someone nearby. I got a nudge of encouragement from some Audax Club Bristol riders at Carhaix – they were forming a group to ride through the night and an invitation was extended to me. However, several of them were riding fixed gear bicycles and this meant we were never going to be matched as the road climbed and fell. It was nice though, to be supported by UK audax riders I’ve met on other events and know through social media.

The route to Brest from Carhaix has a lump in it, a hill if you prefer. It is called Roc’h Trevezel and is a 16km climb, rising a meagre 200-ish metres. The climb is nothing, but the sense of upward-ness for so long was tiring. And it was dark. I saw nothing of the beautiful Brittany scenery, all I saw were swaying rear lights weaving their weary way uphill. Until we reached the top – and then… we plummeted. Or at least I did. I passed everyone. Being a heavier rider means that gravity pays more attention to me than the others, and the road was almost straight, with a great surface and a wide lane. We dropped and continued to drop for kilometre after kilometre, getting colder and colder. As the group careened into a small village, I noticed a local café was open: the call of freshly baked pain au chocolat was irresistible.

As I left, I was refreshed with coffee and pastry, but cold with the pre-dawn light. It wasn’t long before I started to feel a little sleepy, but I knew that if I lay down on the verge, I would fall asleep and wake up cold and damp. I remembered a top tip from Jenny Graham: she holds the record for cycling round the world solo and unsupported. In her book, she describes how to combat sleepiness by standing astride your bike and laying your head on the bars. As you drift off to sleep, your legs relax, and you begin to fall over. This jolt wakes you up as you catch your balance. It was a technique which gave Jenny valuable shut-eye and helped her to keep riding. It worked for me too.

Once the pre-dawn shifted to dawn, and the light strengthened, the hypnotic rear lights and yellow gilets became less of a problem, and I gained energy and speed. So much so, that as I arrived in Brest, I was caught up in a courier style race through the Tuesday morning traffic to the Control Point. Not everyone in Brest had got the memo about the ride and I think a few queuing drivers were surprised to be overtaken by a swarm of cyclists. The Control was a lot further through the town of Brest than I had expected – our racing was extended and involved riding out of the saddle up hills and through multiple roundabouts.

Brest: the halfway point. We are given 40 hours to reach this point and 50 hours to get back. I’d made it by 8:15am on Tuesday: 37 hours after leaving Rambouillet and with only 2 hours of sleep. I was so unbelievably happy at this point: it was early morning and I had energy, I had raced out to Brest and now knew I could tour back. It had taken me 37 hours to get here, and I had 53 hours to return… as far as I was concerned at this moment, I’d done it. The easy bit lay ahead. I stopped for a shower in Brest and changed my cycling shorts and socks for fresh clothes from my luggage – I felt fabulous. On the way back, we crossed Pont Albert Louppe, a cycling and pedestrian bridge over the harbour with a great view of Pont de l’Iroise, the cable-stayed bridge that carries heavy traffic between Brest and Quimper. It is Paris-Brest tradition to stop for the photograph: I met Chris one more time and we took each other’s picture despite the morning sun shining in the camera lens.

It was hilly from this point onwards, but I didn’t care. None of the hills are anything like West Yorkshire and I was touring home, so nothing could bother me or make me anxious. I chose to stop and eat a baguette I’d picked up in Brest while stood in the corner of a field, looking out over another beautiful valley in the morning sunshine. I enjoyed the undulating route back to another secret control at Playben and onwards to get back to Carhaix. I hadn’t been rushing, and I’d also become conscious of my emotional rollercoaster, discovering that I felt weakest and most downhearted in the heat of the late afternoon, or in the pre-dawn. If I could mitigate that, I would have a much more enjoyable ride.

In Landeleau, in the late lunchtime heat, I noticed a small pub just off the route and decided to see if I could get some Coke to drink. Outside, there were two young Frenchmen, backpackers by the look of their heavy rucksacks. I said, “Bonjour” and they replied “Hello”. I smiled and asked if the bar was open. They said yes, but then paused, looked at each other and said to me, “but we have to warn you, it is very strange in there.” I stepped inside cautiously, there was no one around, only the sound of wind and creaky windows. A church bell tolled, and then the most awful howl surrounded me, like a wolf crying out for its pack. The landlord came out and I said, “Un coca-cola s’il vous plait.” He replied, “sure thing, you’re doing this big ride are you?” His strong accent a clear indication of his British roots. As we talked about the ride, about the heat and about running a British pub in France, he explained that he was preparing and testing the sound system for Halloween. I accepted this, despite it being only late August. As I left, I told the two young men outside that there was nothing strange about the pub; all British pubs have spooky mood music, it’s a traditional thing.

I reached Carhaix for the second time at 3:30pm, and decided to get some sleep. Sadly I’d forgotten how chaotic Carhaix was: food was all but sold out in the early afternoon, and the sleeping facilities appeared to be on the far side of a school playing field. I waivered back and forth failing to either eat properly or get sleep. In a fit of frustration, and without sleep I headed back out into the hottest part of the day.

At Glomel, about 20km beyond Carhaix, I found a tiny supermarket called ‘Proxi’, with a picnic bench and umbrella out the front. After buying a pasta salad, a couple of cans of cold drink, and a sandwich, I sat and felt sorry for myself. I wondered if I was going crazy. I’d been riding for 45 hours with only 2 hours sleep. I had 3 hours in hand, and I was wasting it. How on earth was I ever going to get a good night’s sleep. Corinna O’Connor (Four Corners Audax), had joined me for food, but wisely had no time for my self-pity. She told me to cheer up and headed off into the beautiful sunshine. Corinna was right: I got back on my bike and followed in her tyre tracks.

30km later, in Cléguérec, I had an epiphany which changed my entire Paris-Brest experience. The town was having a street party like no other; there was live music, street food, a bar, dancing, and amid all that, people were cheering every cyclist that went past. A friend of mine had told me to make the most of the atmosphere of Paris-Brest, that people often regretted dashing from Control to Control without immersing themselves in the wider spirit of the event. So I stopped again, but this time I wasn’t anxious. I ordered an immense burger and chips from the take-away van, and waited for it to be cooked. I looked at my Brevet Card and finally I understood Paris-Brest. I was in the hands of the French organisers: they were shepherding me through the ride by encouraging me out of Controls and onto the road. My time schedule wasn’t my own – it was theirs. As I surrendered to the full value experience of the event I finally found peace. My afternoon anxiety was gone.

Even with my leisurely pace, and attending the party in Cléguérec, I reached Loudéac with more time in hand than when I’d left Carhaix. My sleeping experience in Loudéac had been good before, so I sought the sleep I had wanted in Carhaix. The camping mattresses were excellent; I had 60 minutes of deep sleep and when I woke, felt refreshed enough to carry on. How can this be? I had only had 3 hours sleep since last Saturday night and yet I was feeling ebullient as I walked through the crowds to find food. Cléguérec and Loudéac had been good to me, and I left in the middle of the night to make my way to Tinténiac once more.

I hadn’t made any new friends while riding, and as three riders from the Pacific Coast Highway Randonneurs caught me, I struck up conversation, hoping they’d be welcoming. They were. They had been practicing a method of keeping each other awake and alert which involved thinking up, and answering quiz questions from 80s popular culture. I joined in, “What were the four characters in The A-Team?” An easy question to answer, but a significant challenge at 2am cycling through France. I think I was riding with Philip Auriemma and Robert & Deirdre Mann. If they remember me, I was the one who tried to explain what a cyclist’s Eddington number is. How you remained awake through that is beyond me.

I arrived in Tinténiac just before dawn on Wednesday, and stuffed my face with breakfast. People were asleep all over the place, wrapped in orange foil emergency blankets. With only 400km remaining my spirits were high: the night had passed and the day lay open before me. I recalled how the outward leg of this ride had been in the afternoon heat and very difficult, but now I was looking forward to my usual morning energy.

The hills were rolling, but I had bags of energy and joy, so I powered along in isolation, using the areo-bars because no one else was around. When I took a wrong turn at a roundabout and everyone I’d passed flowed back past me I eased off and paid more attention. This was perhaps why I spotted “Le Fournil de Baptiste”, a Boulangerie Pâtisserie in Ercé-prés-Liffré. I pulled to one side and went in for a pain au chocolat. I had a new mantra, “Never miss an opportunity for a pain au chocolat”. Several other riders stopped with me and we drank black coffee and ate pastries together. I sat chatting to Franco about the comfort of steel bicycles, he noticed I was riding a Colombus steel bike. He was so excited and told me that he was the engineer responsible for making my bicycle frame. He works for Columbus steel in Italy, and we shared a joyful moment, reuniting my bicycle with its maker.

Leaving Franco to finish his coffee and pastry, I cycled on through the morning sunshine, enjoying the warmth and the gently rolling hills. Everything felt easy at this moment.

I reached Fougères again at 10:30am. 940km covered in 69 hours, with 3 hours sleep. I was aware that the next section was going to be tough: emotionally and physically. The heat of the afternoon beckoned, and I had experience of this rollercoaster and knew that I would be able to get through if I kept my spirits up. Around 12:30pm, I tweeted a picture of my lunch. I had stopped at a bar on a long straight stretch of road, and ordered Orangina alongside a steak and salad. I sat outside in the sunshine eating my lunch.

It took a little while longer than expected because I kept nodding off as I tried to eat. My head was on wobble mode with my neck, not managing to stay in one place. I have no idea where I was, but after one particularly noticeable doze I finished my drink and continued.

I expected to make stops for rest or refreshment in the heat, and decided that if I could make Villaines-la-Juhel during the afternoon, I would treat myself to another sleep there before facing the final night of the ride.

Villaines-la-Juhel was the most emotional experience of the ride: it felt like literally the entire town had turned out to encourage all the riders. In the same way that the finishing straight of a race is cordoned off, the approach to the Control was along a stretch of road lined by cheering crowds. I rolled in between two groups on my own at about 5:30pm, and the crowds were shouting as loudly for me as for anyone. I nearly cried as I was swept up in waves of emotion. These people knew what we were doing and were cheering for us to succeed.

I needed some sleep. I didn’t bother with food; I could barely articulate myself as I sought out the sleeping arrangements. There was a sports hall with a red crash mat on the floor. That was mine for an hour. All I wanted was one hour. I fell straight to sleep and woke up refreshed after 60 minutes, with the volunteer just coming to get me. It was the early evening and for the first time on my ride I felt cooler. I put leg warmers on to keep myself feeling cosy in the evening chill. A search of my surroundings revealed I had lost my bike computer. I had no idea why I’d taken it off the bike at all anyway, perhaps the crowds, perhaps the tiredness – but now it was lost. A trip to the lost and found sorted me out and in moments I had my GPS cycle computer returned to me. This event was proving to be the safest place to leave a bike and equipment unattended.

The dining experience was bizarre, because there was plenty of food, it just didn’t make sense that I was eating it all at the same time. Breakfast with pasta. Fizzy drinks and coffee. I wasn’t complaining, I needed the calories. I only had another 200km to ride, but another night lay ahead of me. I left Villaines-la-Juhel confident I would finish, and happy that I could probably get some more sleep at each of the next stops.

The ride to Mortagne-au-Perche was in the pitch black. The leg warmers I had put on were a mistake because the night was not as cold as I’d imagined when I’d woken up. I didn’t want to stop and take them off though, because I didn’t want to get cold. This was Wednesday night. I had now been riding for 72 hours; from Sunday evening through Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday with only 4 hours sleep. I was in the heart of the Paris-Brest experience. Occasionally I stopped for food or hot drinks at the pop-up roadside cafes, run by locals who had continued to cheer us on day and night for four days. Their enthusiasm for our endurance cycling was unbelievable, especially coming from the UK where cycling is seen as poor person’s transport, or child’s pastime.

I remember a group of four young Frenchmen in a car screeching to a halt in front of us at 2am-ish. They leaned out the window to shout at us, “Bon Courage!”, “Allez, Allez, Allez!”, “Bon route!”. What a difference with audax back home where the best we can hope for is, “Are you doing a charity ride mate?”

I got to Mortagne-au-Perche just past midnight, and into Thursday morning. The darkest part of the night. I wondered if another hour’s sleep would help. It did not. The only place left to lie down was on a paper-thin roll mat on a concrete floor. I slept immediately and woke an hour later full of aches and pains for the first time. I realised how physically good I had been feeling until that point.

I was feeling sorry for myself as I left Mortagne-au-Perche, and the coldest darkest part of the night was ahead as I cycled to Dreux. I found company, riders to talk to, to listen to. No one was moving very fast. The road was flat and it was pitch black around us.

Once or twice I tried Jenny Graham’s trick for power napping astride the bike. As the dawn came up I rolled into Dreux. The last stop before the finish. I looked around and felt that stopping would be a time-wasting mistake, so I just got my card stamped and carried on.

Thursday, 7am. The familiar burst of energy came with the morning light. I was feeling in high spirits once more. The headwind on the flat sections was not going to bother me, as I found companions to share the load with. We took it in turns to ride into the wind, giving each other shelter. I had more and more energy the further we rode, and I had a plan.

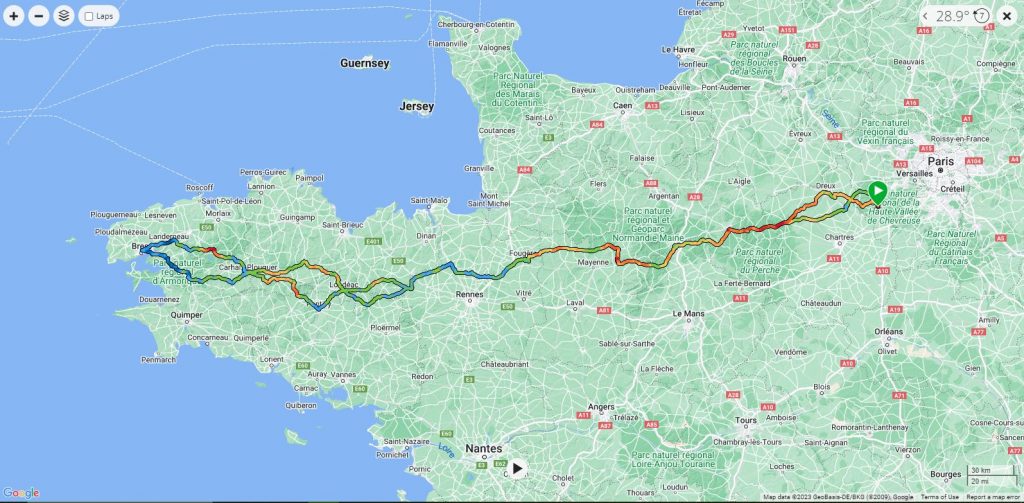

With 8km to go to the finish line, I called into our Air BnB. I had a shower, I put on fresh cycling clothes. I rode the final 8km feeling wonderful and looking fresh. I crossed the finish line back in Rambouillet 86 hours and 1230km after leaving: surprised at how physically good I was feeling.

My friends from the UK audaxing scene were hanging out having a beer, food, chatting about their rides and cheering the remaining riders across the line. As it began to rain, I cycled home to the Air BnB and called my wife – and then I slept. 12 hours blissful, comfortable sleep, and when I woke… can you believe I was keen to ride my bicycle again.

My cycle computer tells me I was only actually cycling for 58 hours. I know I slept for 5 hours, which brings the time up to 63 hours. What on earth was I doing for the other 23 hours? Oh yes, I remember: asking for a medical exemption, going to an acid house party, having a meltdown beside the road, arguing about how best to treat scalded fingers, taking photographs, meeting werewolves in the pub and eating street food at roadside parties. I may also have taught Americans how to calculate their Eddington number.

At last my memories are beginning to make sense.

I’m deeply grateful to my wife for the six months of patience as I prepared, qualified and participated in Paris Brest Paris. To my Audax UK friends for their encouragement and support during the ride. To the French for being so totally awesome. To God, for not losing me in the long watches of the night.

I’m excited to return for the next edition of Paris Brest Paris, in 2027. I think I might know what I’m doing – and I’ll be one of the experienced riders.

Photographs taken with a Boots 350AF compact camera, with Kodak UltraMax 400, 35mm film. One or two were from a smartphone.